During the past months, I’ve been lucky to have the chance to write more Rust code for work and also for fun. Rust continues to be an interesting and fun language for me. Not everything is perfect, of course. Today I wanted to write about something that has bothered me since day one. It’s definitely not a huge problem, more like a slight annoyance, but I wanted to write about it anyway because it relates to the design of the Rust language and its standard library, which is a topic that I find interesting. So here it goes:

There are tons of methods in the standard library that return concrete types instead of abstractions (i.e. traits). These typically have the same name as the method itself, just with different casing. This often makes the signature of methods less intuitive.

Let's take a look at an example. Strings have a method called chars(). This method has the following signature:

pub fn chars(&self) -> Chars<'_>

Ok, so chars() returns Chars, that doesn't tell me much. It sounds like I'm getting the characters of the string, but I have no idea if it's an array, a slice, an iterator, or something else. Let's look at the documentation of the function:

Returns an iterator over the chars of a string slice.

As a string slice consists of valid UTF-8, we can iterate through a string slice by char. This method returns such an iterator.

It's important to remember that char represents a Unicode Scalar Value, and might not match your idea of what a 'character' is. Iteration over grapheme clusters may be what you actually want. This functionality is not provided by Rust's standard library, check crates.io instead.

Alright, not a big problem, isn't it? Well, it still bothers me a little bit. The reason is that one of the advantages of adding type annotations in statically typed languages is supposedly that it makes the code more self-documenting. The signature should allow us to have an idea of what the function or method does without requiring extra documentation.

Consider for a moment that the signature of this function was something like this instead:

pub fn chars(&self) -> impl Iterator<Item=char>

We can argue that this is more self-documenting than the previous signature. It's easier to understand what the function does just by looking at it. We still need the documentation for certain details, for example, the fact that this iterates over Unicode scalars and not grapheme clusters, but I'd argue that even this is obvious from the signature.

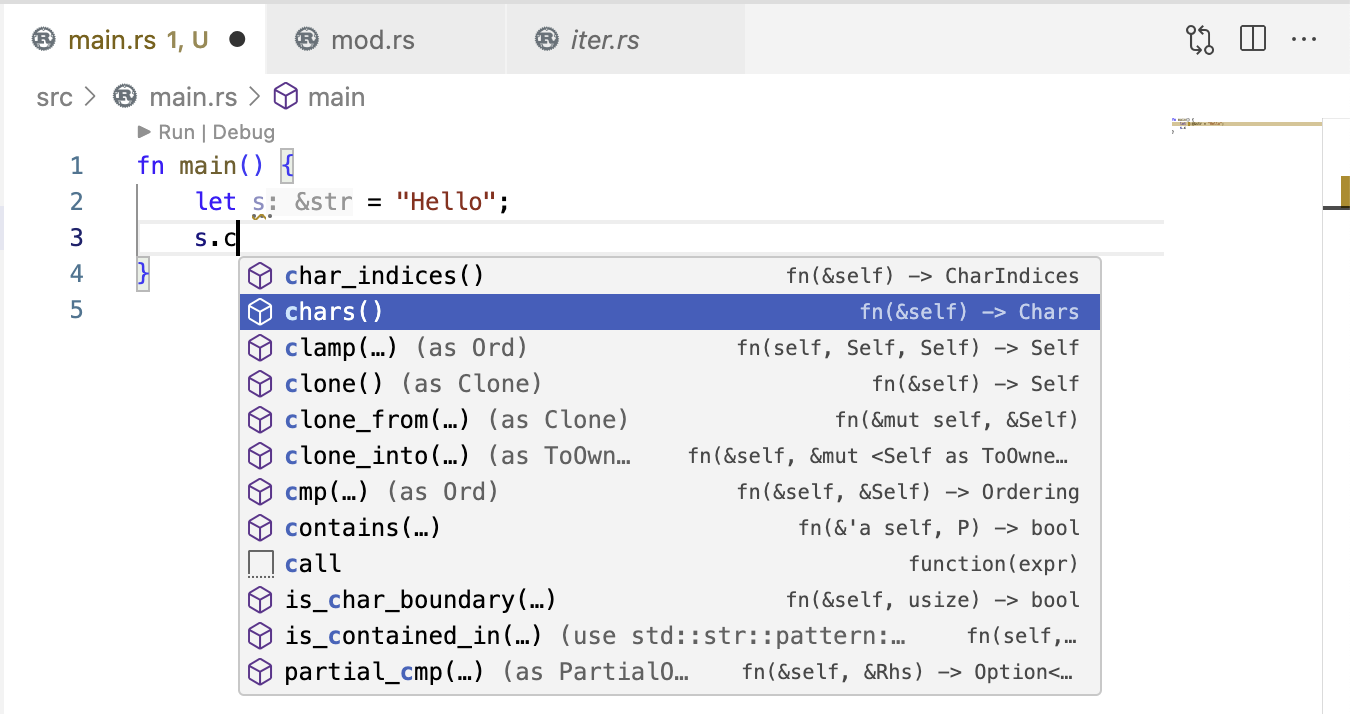

Why are self-documenting signatures important? Well, it's very common to learn APIs directly while coding and looking at the completion suggestions. For example, in VS Code, this is what we get in completion:

We only have signatures here and Chars doesn't tell us much.

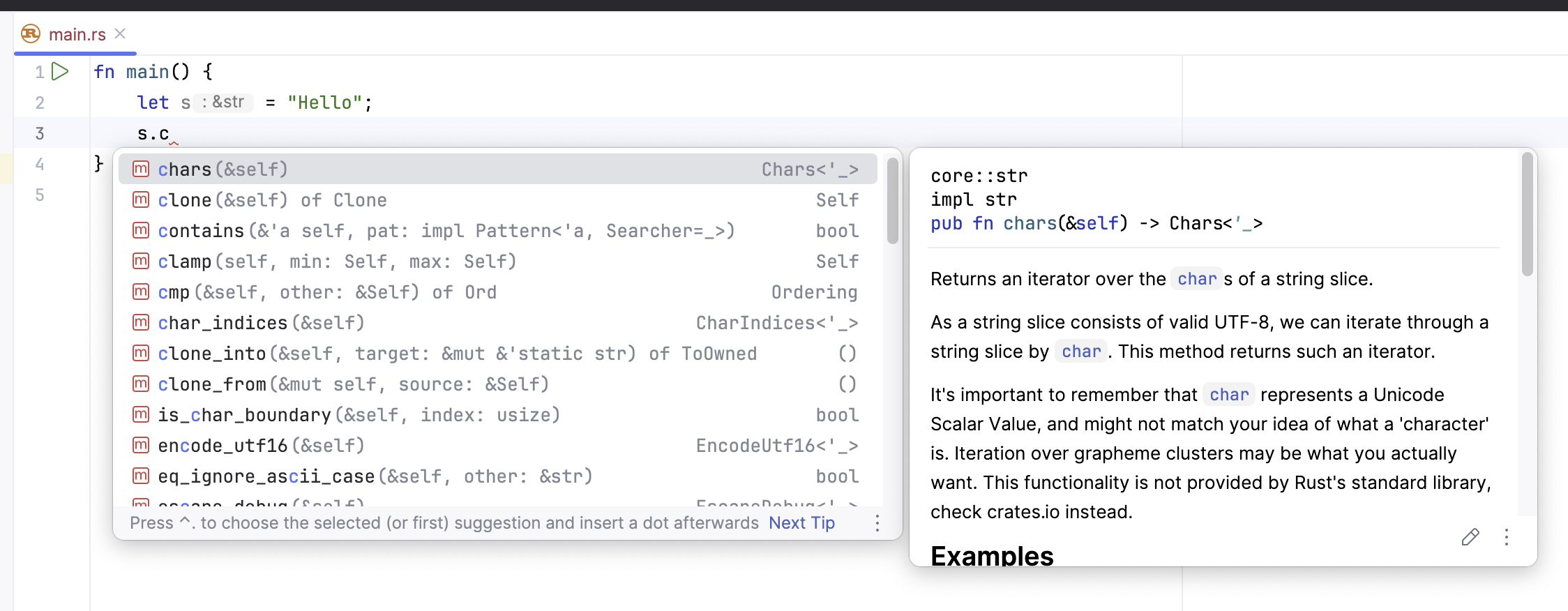

RustRover does a slightly better job here, showing us the documentation for the selected option:

Better, but only partially useful.

I was wondering what is the reason behind returning concrete types in Rust’s standard library instead of abstractions. In terms of best practices, different programming language communities have different opinions. In Java, the most accepted position is to accept and return abstractions in APIs as much as possible. But in the Go community, the suggested practice is to accept interfaces but return structs.

I prefer the idea of returning abstractions when those already exist. This not only makes the code more self-documenting, but it also gives the flexibility to eventually change the implementation without breaking the API. It also reduces the API surface as we don't have to expose an extra type.

It's possible that all these methods existed way before Rust could specify abstractions as return types of functions efficiently. Return position impl traits (RPIT) were only introduced in Rust 1.26. Before that, the only way to do something similar required Box<dyn Trait> which would add some costs in the form of allocations and dynamic dispatch.

But that's not the whole story. The actual reason is that Chars is much more than just Iterator<Item=char>. If we look at the source code, we see that Chars not only implements that, but also DoubleEndedIterator, FusedIterator and Debug.

Perhaps we could still have a signature like this:

fn chars(s: &str) -> impl DoubleEndedIterator<Item=char> + FusedIterator + Debug

Yes, it's more self-documenting, but it starts to get big and noisy. It likely won't fit in a completion dialog anymore.

But even this would not work, because Chars also has an inherent implementation that provides the as_str() method. So I guess that there is no choice but to use a concrete type in this case.

If we have no choice but to use a concrete type, is there any way to make this a little bit more intuitive to use? I think naming would have helped a lot here. Had Chars been named CharIterator instead, this signature would have been more intuitive. As we all know, naming is definitely one of the hardest things in computer science. But there are also cases where naming is not going to be enough to make a signature alone self-documenting.

We could argue that having self-documenting code doesn't necessarily imply that everything should be immediately obvious just from the signature. After all, names are labels that we put on things, and as long as we can look at the definition of those names, our code is going to be self-documenting. In fact, when I'm learning a new Rust API, this is what I do, I find a type with a name I don't understand, and I go to the definition to learn what it is.

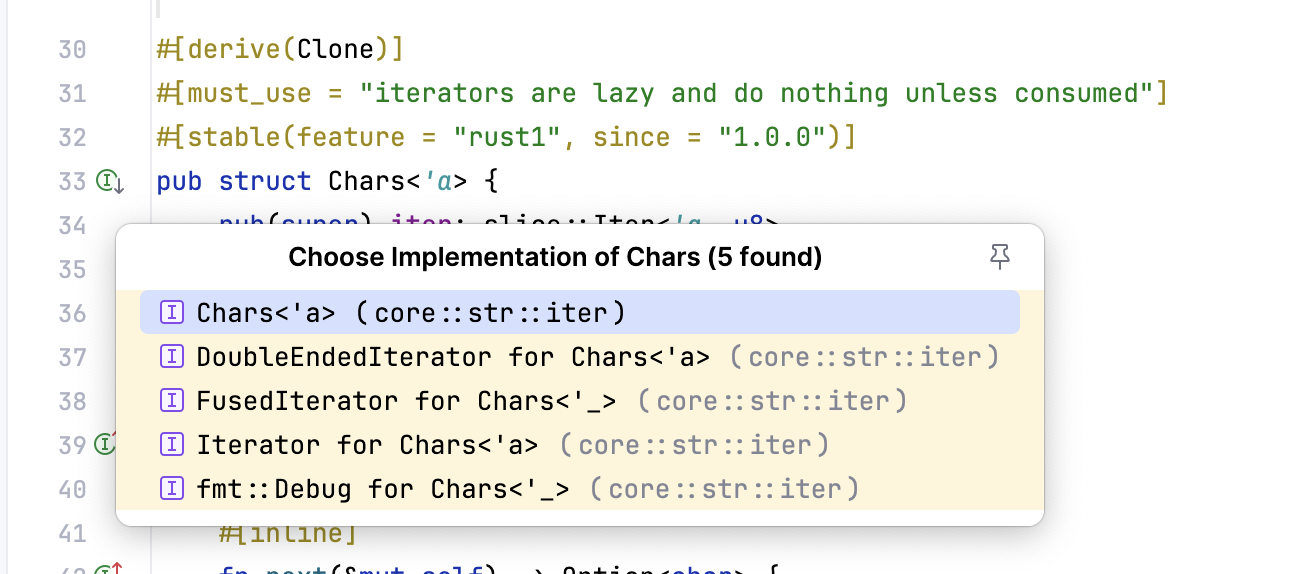

And this brings me to my next pain point when learning Rust APIs: If I find a name that I don't understand (like Chars) and I jump to its definition, I often find something like this:

pub struct Chars<'a> {

pub(super) iter: slice::Iter<'a, u8>,

}

I see a struct definition with a non-public field (yes, even when the field has a pub keyword, it doesn't mean it's public, but I would need another post to talk about visibility modifiers in Rust). This definition doesn't tell me what Chars can do, or in other words, what traits are implemented for this. In particular, it doesn't tell me that Chars is an Iterator<Item=char>. The way the trait system works is that traits can be implemented almost everywhere. So the trait implementations are scattered across the code.

In some other languages, it's easier to recognize what interfaces a type implements. For example, in C#, there is a method of string called GetEnumerator(). It's very similar to chars() in Rust. The signature looks like this:

public CharEnumerator GetEnumerator ()

The first thing to notice is that they also have a concrete type as return. However, their naming is slightly better, it's clear that this type is an Enumerator (which is the way C# calls Iterators). Now if we go to the definition of CharEnumerator, we get this:

public sealed class CharEnumerator :

IEnumerator, IEnumerator<char>, IDisposable, ICloneable

{ ... }

The definition of the concrete type explicitly states which interfaces it implements. We don't need to search through the code to figure out what CharEnumerator is.

Now, don't get me wrong, I really like Rust's trait system. I think it's very elegant and it has a lot of advantages over more restrictive systems such as the one in C#. But there is no doubt that one of the disadvantages of this flexibility is that it affects the self-documenting property of the type system.

So, back to Rust, how can we know what Chars is? One option is looking at the documentation, which includes a convenient list of traits implemented by this type. But again, this list is incomplete, because new traits and implementation could be added by the user crate of the type.

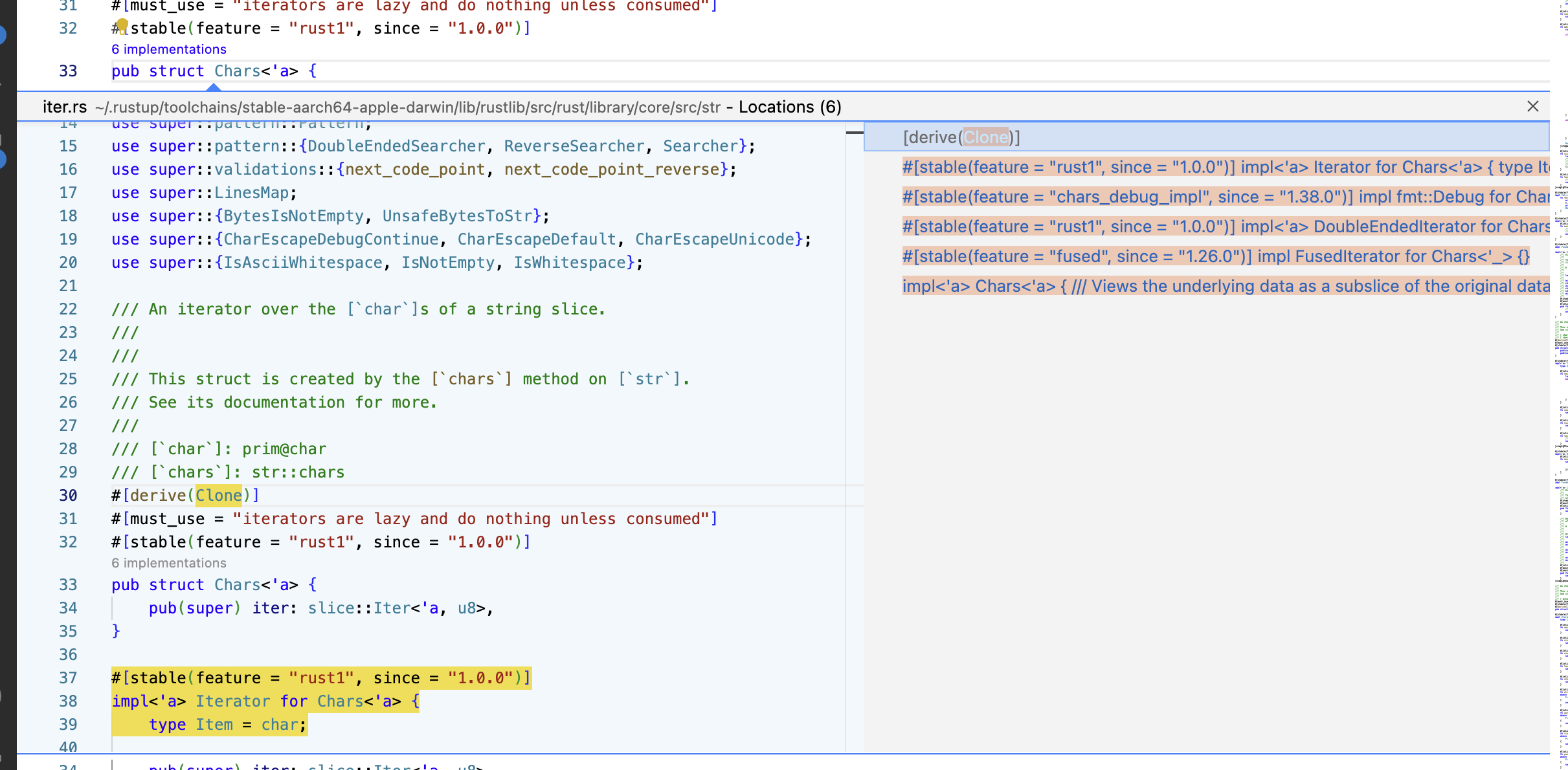

IDEs can definitely help here. RustRover shows an icon next to the struct definition listing the implementations for this type:

VS Code also shows an implementations lens right above the struct definition, although it's quite less readable, in my opinion:

Both IDEs are missing a bunch of blanket implementations. For example, the fact that Chars implements IntoIterator because IntoIterator is implemented for every Iterator.

All this can be slightly worse in some cases. Let's look at another example of the standard library. The split method of strings. The signature is:

pub fn split<'a, P: Pattern<'a>>(&'a self, pat: P) -> Split<'a, P>

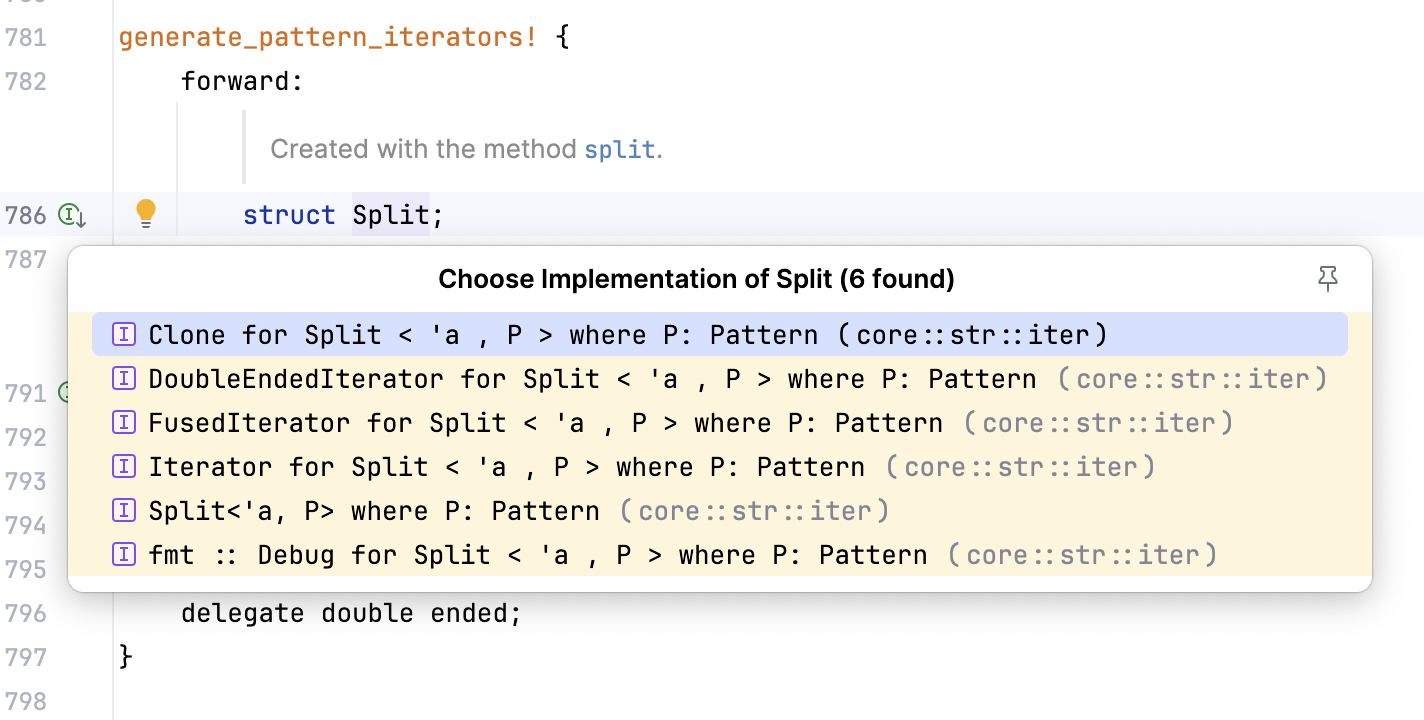

Again we have a return type named as the method, but this time, when trying to go to the definition we find this:

generate_pattern_iterators! {

forward: /// Created with the method [`split`].

///

/// [`split`]: str::split

struct Split;

reverse: /// Created with the method [`rsplit`].

///

/// [`rsplit`]: str::rsplit

struct RSplit;

stability: #[stable(feature = "rust1", since = "1.0.0")]

internal: SplitInternal

yielding (&'a str);

delegate double ended;

}

The Split struct is not written directly, but it is actually generated by a macro, which also generates a bunch of implementations for it. Types and implementations that are generated by macros is another common theme in the Rust standard library. Of course you can go and read the macro definition, but I find reading Rust's declarative macros not very pleasant.

IDEs can help us again by showing us the expansion of the macro. RustRover is even smart enough to show us the implementations list of the struct from the un expanded macro:

But it's undeniable that macro generated types hurt the self-documenting property of the type system as well.

Is there any way to improve things? I don't want Rust to change its trait system or lose macros. These are great and powerful features, even if they have some drawbacks. Besides my previous suggestion of improving naming, which I think goes a long way, IDEs can help a lot too. They could have an easy way of showing all the implemented traits of a given type, including blanket ones. This could be shown while hovering a type, but also in documentation pop ups for signatures. Perhaps there is also a way of showing some compact trait information in the signatures of completion items.

Finally, perhaps it's possible to show a summary of what types and impls a macro call generates. Maybe even for derive macros as well. When a language's type system is so flexible, and there are so many tools for meta-programming, the help of the IDEs becomes extremely valuable. RustRover and VS Code + Rust Analyzer already do some useful things, but I think they are still in their infancy. I'm looking forward for these IDEs to mature and improve the coding experience for Rust.